Ocean Mining — Gerard Barron

Let’s start with a question: What do Manganese, Nickel, Copper, and Cobalt have in common?

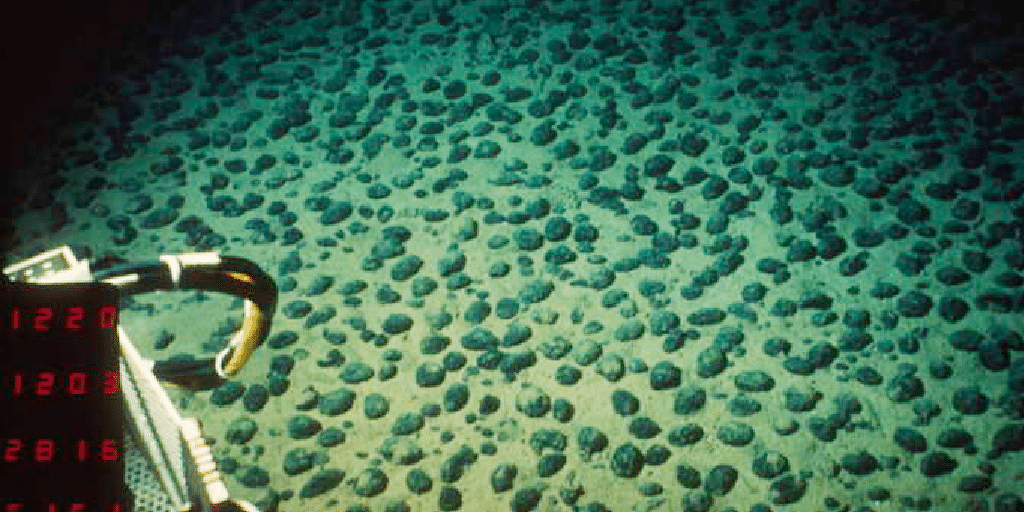

These four metals have two things in common. First, they are all needed to produce electrical batteries. As the world moves away from burning fossil fuels for energy, electric power will replace it. And while there are many clean ways to create electricity, that energy needs to be stored. That means we’ll need a lot of batteries. Secondly, these four metals are all found in large amounts in dark, lumpy, potato-sized rocks called Manganese Nodules. Believe it or not, these rocks may help reduce the effects of Climate Change, Deforestation, Mountaintop Removal and Strip-mining, and many other environmental problems.

You may be asking, “So why aren’t we using them?” The answer is simple: Manganese Nodules are only found at the bottom of the ocean. They are most often found at depths below 13,000 feet (that’s almost 2 ½ miles!). These nodules were discovered in 1868, but it wasn’t until almost one hundred years later that nations and industries took notice and thought of using these resources. But there have been two major barriers.

The first barrier has been technological. 13,000 feet is a long way under water. Of course, this presents challenges that need to be solved before industrial-scale mining is possible. As the Fourth Industrial Revolution progresses, scientists and engineers are on the case. Innovations in robotics, GPS navigation, drone, and remote piloting have made deep ocean mining safer and more practical. As technology advances, undersea mining will become even more practical. Most of the development in this area is being done by private companies like DeepGreen under the leadership of entrepreneurs like Gerard Barron.

The second barrier has been legal. By the United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Sea, all countries have an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). This zone extends 200 miles from their coast. This means that a country can control economic activities, such as fishing or mining, up to 200 miles from their shore. But areas past the EEZ were “International Waters” where there were no rights to own resources. Yet, only a few countries have set up laws to support undersea mining. New Zealand has begun the process. Papua New Guinea has recently begun licensing mining in its EEZ. In 1994, the United Nations created the International Seabed Authority (ISA). The ISA was created to ensure the rights and duties of nations and companies beyond the EEZ. The ISA also creates a “land bank” system where small nations, such as Kiribati and Naru, can sponsor mining activity. Foreign companies do the mining, Kiribati and Naru share the profits. The International Seabed Authority has final authority over who can mine, how much, where, and when.

The promise of undersea mining lies not only in the resources but in the opportunity to get to those resources through sustainable mining practices. Humans have been mining for over 40,000 years, and mining for metals for 10,000. To mine on land means that the material has to blasted or carved out of the rock. This leaves behind huge amounts of waste products, many of them toxic. Mining can also lead to deforestation, water pollution, and soil pollution. With such a long history of mining, people have exploited all of the easy-to-get-to resources. To find new sources of metal on land requires going into pristine areas, such as deep rain forests or into conflict zones. For example, two-thirds of the world’s cobalt (a metal contained in Manganese Nodules) is currently mined in the Congo region, much of it with child labor.

Manganese Nodules are rocks that lie on the ocean floor. They can be scooped up and sent to the surface without any waste product left behind. Almost every metal in a nodule can be recovered and used. There would be little to no waste in processing the nodules into useful material. This is not to say undersea mining is completely without impact on the environment. The process will stir up the dust on the ocean floor. The undersea thermal vents that cause the nodules to form are unique ecosystems themselves. They will need to be kept protected from harm. But environmentally-minded entrepreneurs Gerard Barron and his company DeepGreen are on record as pushing for strict regulation of this new industry. Environmental impact studies have been done and more are planned. Barron believes in the “Precautionary Principle.” The Precautionary Principle states that if an action is to be taken, the person who wants to take the action is responsible for ensuring the action will not (or is highly unlikely) to result in harm before the action is taken. The ISA and many nations involved also hold to that principle. Although, sadly, not the United States which has not signed on. But with the ISA and other agreements, anyone who wants to collect the ocean’s metals will have to do so responsibly.

Journalist and environmentalist Philippe Cousteau once stated that until the second half of the 20th Century, most people thought of the ocean as “something we took our food out of and dumped our trash into.” Today there is a growing awareness that taking too much food out of the ocean and dumping our trash into it leads to terrible results. When that knowledge is coupled with understanding of how to engage in sustainable undersea mining and practices that allow us to use resources responsibly, one begins to think there may be hope for us and our relationship with the oceans after all.

— Luis L.

Hope save the anmals